The prospect of billions of dollars pouring into hydrogen projects threatens to distract leaders from domestic crises Today the rich deep blue of the Mediterranean Sea serves as the incongruous backdrop for thousands of tragic journeys by refugees and migrants heading north toward Europe. On June 14, 2023, a refugee boat capsized off the coast of Greece and left hundreds dead. In 2022, no fewer than 160,000 people attempted to cross miles of open water, often in overcrowded or makeshift boats, according to the UNHCR, the United Nations refugee agency. Almost 40 percent of them were from Tunisia or Egypt. More than 2,300 died.

The migrants were desperately seeking safety and economic opportunity, and thousands more continue to risk their lives every day for the same reason. The flow of migrants has raised tensions between the Northern Rim and the Southern Rim of the Mediterranean, a body of water that has served as the crossroads between Eastern and Western civilizations for millennia.

Even as tensions over migration run high, the Northern Rim and the Southern Rim have renewed their cooperation over energy issues. In addition to traditional oil and gas exporters such as Algeria and Libya, other nations, including Egypt, Lebanon, Israel, and Mauritania, are poised to get in on the action, thanks to several major fossil fuel discoveries.

Amid the global energy transition, investors are anxious to pour billions of dollars into many of these countries to turn the new fossil fuel finds into hydrogen. The element is the key feedstock for fuel cells, which use chemical reactions to generate electricity cleanly, with water as the main byproduct. Notwithstanding the considerable technological challenges ahead, demand for the gas in Europe and elsewhere is widely expected to surge as vehicles, factories, and other energy users seek to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

For Southern Rim nations, however, this tantalizing opportunity for economic development risks turning into just another Sahara mirage. That’s because the hype surrounding hydrogen may continue to distract the regions’ leaders from addressing the tough domestic social issues that are behind the migration crisis. If the technology does become viable, revenue from hydrogen exports to Europe could just perpetuate rent-seeking behavior by political and economic elites at the expense of their own citizens.

Certainly, the fallout from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine helped cement energy cooperation between the two sides of the Mediterranean. The war put energy security at the top of the policy agenda as European nations scrambled to replace Russia’s natural gas and oil. More resources from the Southern Rim flowed north, generating foreign exchange revenue.

Political leaders from Italy, France, and Germany visited their counterparts in Algeria, Egypt, Libya, and Mauritania to expand cooperation on energy issues. These high-profile contacts resulted in promises of more fossil fuel exports and new investments in extraction and transportation, including pipelines. Such investments will ensure that fossil fuels from the Southern Rim keep flowing north to Europe.

New focus on renewables

Critics have blasted Europe’s advanced economies for their not-in-my-backyard policies of relying on developing economies to do the dirty work of producing fossil fuels and extracting minerals critical for the energy transition. In addition to the climate and environmental risks, the Southern Rim and the rest of Africa face the danger of being left behind once Europe resolves its energy security issues. The economic concentration around fossil fuels and associated capital investments expose these nations to the risk of stranded assets or the threat of stringent restrictions on fossil fuel trade.

The European Union has made great strides in advancing its energy transition. Investments in renewable energy have increased rapidly, but the race to replace energy from Russia also showed how hard it is to quickly ramp up renewable and other cleaner energy sources. Still, the formidable decline in the cost of producing renewable energy has been a key driver behind these investments.

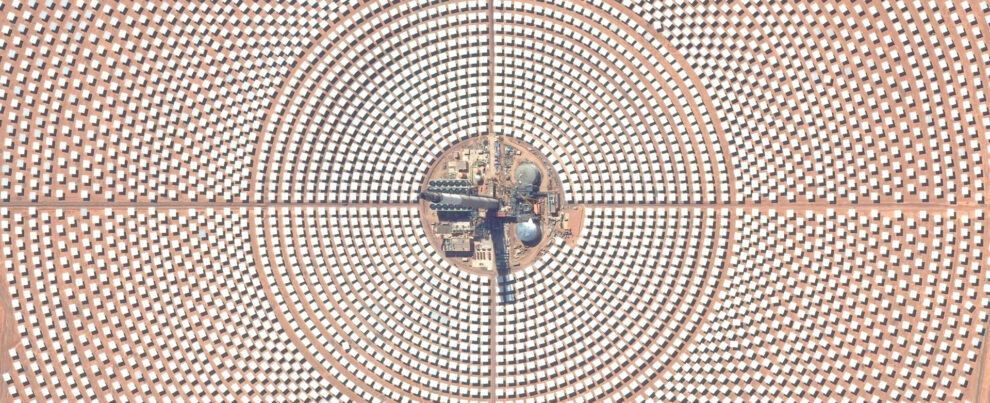

As for the Southern Rim, nations there will face greater macroeconomic and financial challenges in the energy transition, partly because of the relatively higher cost of capital. Some Southern Rim nations have made progress toward reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Egypt and Morocco are ramping up renewable energy. Morocco built the Noor-Ouarzazate complex, the world’s largest concentrated solar power plant, covering 3,000 hectares. Others, like Algeria and Mauritania, are gearing up to install large solar and wind projects.

These days hydrogen is at the center of attention in the Mediterranean region. Hydrogen is easily the most abundant element in the universe, offers a clean source of energy, and can come from a variety of sources. “Gray hydrogen” is produced from natural gas but without carbon capture and storage. When carbon capture and storage are added, the hydrogen is labeled “blue,” but the costs are higher. “Green hydrogen” is produced using nuclear power, biomass, or renewable energy like solar or wind. Its costs are still relatively high.

Enthusiasm around green hydrogen is raging. Projects costing billions of dollars are under consideration in Mauritania, Algeria, Egypt, and other countries. A German developer and Mauritania signed a memorandum of understanding with a consortium for a $34 billion project with annual capacity of 8 million tons of green hydrogen and related products.

Hydrogen projects could help keep energy flowing from the Southern Rim to the Northern Rim. The infrastructure to transport hydrogen is already under development, although projects so far focus on the intra-European market. A large chunk of the prospective hydrogen investments may end up in Europe, with Italy and Spain gearing up to become big producers. Portugal, Spain, France, and Germany signed an agreement to build a Mediterranean pipeline that would supply 10 percent of the EU’s hydrogen by 2030. The energy ministries of Italy, Germany, and Austria signed a letter of support for the development of a hydrogen-ready pipeline between North Africa and Europe involving Italy’s gas grid operator.

Such mega investments could have important macroeconomic implications, especially for the smaller and less diversified economies of the Southern Rim. Challenges will involve exchange rate appreciation and current account swings from deficit to surplus. Policymakers will also have to tread carefully because of contingent liabilities associated with large projects, such as failure or abandonment.

While the shift in geopolitics accelerated by Russia’s war in Ukraine is furthering energy integration across the Mediterranean, the new push for industrial policy and economic sovereignty in Europe is working to limit integration. These are new risks North African countries will have to manage, and they suggest the need for greater attention to addressing domestic issues.

Domestic issues

Big hydrogen projects hold out the promise of generating revenues that could help address the needs of Southern Rim citizens. Access to reliable and abundant energy is surely a building block for industrializing economies. Yet, if history is any guide, the abundance of energy alone is not sufficient to achieve economic development. Countries in the Southern Rim have a lot on their plates, and social cohesion is at stake. The authorities need to regain the confidence of their youth and address long-standing domestic issues, whether social, economic, or regional. The desperation of young people from the Southern Rim drives them to risk their lives crossing the Mediterranean, signaling the pervasiveness of these issues.

There are, of course, great differences between oil-exporting and oil-importing Southern Rim nations. Importing nations such as Morocco and Egypt have overhauled or removed fuel subsidies or price controls, with accompanying mitigation measures such as cash or in-kind transfers to ease the impact on poor households. Oil-exporting countries such as Algeria and Libya have tended to stick with subsidies despite their high economic and environmental costs. In economies with little political accountability, this reflects an enduring social contract under which citizens accept subsidies and look the other way as political and economic elites capture the revenues generated by fossil fuels and now, most likely, hydrogen.

Across the Southern Rim, distrust of government and perceptions of corruption remain high. The lack of economic opportunities stems from the lack of a dynamic private sector. Unemployment is higher for individuals with more education than for those with less. In many of these countries, the legacy of a state-administered economy with large, government-owned enterprises crowds out independent businesses and creates the conditions for a parallel informal economy.

And state-owned banks have long underpinned shadowy flows of funds that support the state-owned enterprises and limit fair competition. In countries where the footprint of the state is less significant, it is a crony private sector that typically captures the wealth, distorting competition. Whether in systems where state-owned enterprises or a crony private sector dominates, millions of young people have been left behind. In both cases, the perception of corruption and rampant inequality are gravely undermining social cohesion.

The prospect of hydrogen exports may help improve external fund balances. But it may also reinforce rent-seeking activities to the detriment of other aspects of a nation’s economy. To avoid repeating past mistakes, the sector must show utmost transparency to limit corruption.

Authorities should also try to maximize not only the revenues they derive from hydrogen production but also the benefits for citizens, including localization policies. An energy sector that is geared for exports will not yield the kinds of jobs that will be needed for young people, who represent the majority of the population in the Southern Rim.

It is thus important to carry out reforms that go beyond the energy sector. Restructuring must be broader and aimed at removing roadblocks to creating decent jobs for young people. That would help address their growing sense of desperation. But carrying out such changes in the context of widespread distrust isn’t easy.

The sequencing of reform could build trust. In a nutshell, changes must start with the political and administrative elites and cronies “walking the talk” before introducing changes that affect the broader population. Specifically, it will help to get rid of corporate subsidies stemming from import monopolies and more generally to promote fair competition by limiting the abuse of dominant positions by state-owned enterprises or cronyism. In addition to greater transparency in the energy sector, the use of distributed solar power would blur the distinction between consumers and producers. That may make citizens more accepting of evolving market prices. Only then could labor market restructuring and exchange rate stabilization bear fruit.

Among nations on the Southern Rim, regional cooperation is at an all-time low. Rekindling cooperation would help create a larger market that would be more attractive for new investment, similarly to the development of the EU. A coming-together of North African nations could help in the renegotiation of better trade deals with EU partners and others. Rather than grasping at the mirage of collecting prospective rents from hydrogen exports, leaders in the Southern Rim should pay more attention to building trust at home and providing opportunities to the young people who are voting with their feet at the peril of their own lives.

Source: IMF