North African cuisine is overdue for greater attention in the West.

The tiny steamed semolina balls of couscous are no stranger to the European and American palates, and other dishes or condiments, such as the eggs poached tomato stew shakshuka or the fiery chile harissa are similarly widely known.

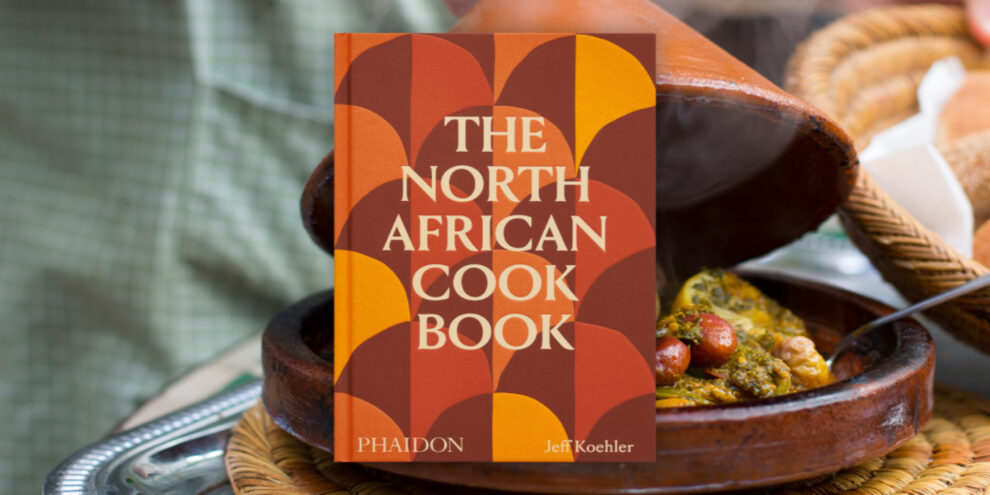

However, most of the cuisine of the Maghreb is still awaiting mainstream discovery. Thankfully, the art and culinary publisher Phaidon has just released a collection of Maghrebi food by the American writer and cook Jeff Koehler.

“Gastronomic migrations between the north and south Mediterranean have long shaped Maghrebi cuisine”

The North African Cookbook, lest there’s any confusion, is not concerned with Egyptian gastronomy. Koehler playfully borrows the late Tunisian president Habib Bourguiba’s definition of the Maghreb: the land where people eat couscous.

In other words, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and western Libya — and in this massive region larger than the European Union, what’s served on the table is rooted in Berber, Arab, Jewish, Ottoman, and northern Mediterranean cultures.

A resident of Spain, Koehler’s culinary infatuation with North Africa began in Morocco. As he ventured eastward, he was delighted by the diversity of the region’s cooking.

This variety was twofold: a diverse array of dishes but also countless dishes prepared in endless ways. Take couscous, which exemplifies North Africa’s culinary heritage more than any other staple. “There are as many couscous recipes as there households,” Koehler relates, “reflecting the landscape, the season and a family’s economic resources.”

![Pan-cooked semolina date bars [Phaidon]](https://www.newarab.com/sites/default/files/2023-06/Screenshot%202023-06-13%20182222_0.png)

In Tunisia, couscous topped with grouper fish is a national dish but lamb reigns supreme in Algeria while Moroccan couscous features a delectable spice mix of saffron (or turmeric), ginger, cinnamon, sweet paprika, and cumin. Libyan couscous is famous for its busla topping of onions and chickpeas with cinnamon and cloves.

As a Tunisian, the numerous couscous recipes relayed by Koehler were mainly unfamiliar to me as most varieties tend to be local traditions. It is in France where one can find the greatest variety of couscous thanks to Arab, Jewish, and Berber migration and the Pied-Noirs (French Algerians) who repatriated an abiding love for communal food. This culinary exchange has gone both ways.

The Sicilian community in Tunisia under French colonial rule forever changed the eating habits of Tunisians, who today consume more pasta per capita than any country bar Italy. But Tunisian plates of pasta are far from imitation of Sicily’s own.

Tunisians boil pasta beyond al dente for a more tender bite and often add a spoonful of spicy harissa to the sauce. One popular square-shaped pasta, nwasser, is prepared akin to the method used for couscous: steamed before it is mixed with sauce.

The North African Cookbook features several Tunsian seafood pasta recipes — a testament to the central role the coastline plays in the gastronomy of this most Mediterranean of Maghrebi countries — alongside makrouna arbi: a hot chicken, potatoes, and chickpeas dish that translate into “Arab pasta” as if to say, as Koehler writes, “it is Tunisia’s own and not an Italian import.”

“A striking thing about North African cuisine is the artistic presentation of dishes inspired by Islamic geometric patterns and Arabic calligraphy”

Gastronomic migrations between the north and south Mediterranean have long shaped Maghrebi cuisine. Under Muslim rule, the Iberian Peninsula was deeply connected with North Africa for 800 years.

The conquering North African Moors introduced a host of new ingredients to Spain and Portugal: including pomegranates, eggplants, oranges, hazelnuts, figs, and, of course, couscous. The 13th-century The Anonymous Andalusian Cookbook relates that the “moistened couscous is known by the whole world.”

![Sweet lamb with prunes and dried apricots [Phaidon]](https://www.newarab.com/sites/default/files/2023-06/Screenshot%202023-06-13%20182203.png)

After the Christian Reconquista, roughly one million Muslims and Jews resettled in the Maghreb and brought with them new methods for preserving fruits and vegetables and popularized orange blossom water, today a common ingredient in the region’s desserts.

They also carried with them new vegetables from the Spanish colonies: tomatoes, peppers, and potatoes amongst others. Moreover, they sparked a culinary renaissance by introducing the elevated cooking techniques refined in the wealthy kitchens of al-Andalus.

Royal kitchens can play an important role in a nation’s gastronomy; in the Maghreb, this is mainly seen in Morocco where successive dynasties across several capitals refined Moroccan cuisine leading to the complex spices present in the country’s dishes.

The story goes that in the early 1500s, Spanish soldiers near the port of Oran demanded something to eat and a hapless cook had nothing more than chickpeas power and water to mix and bake.

When the tart was ready, he instructed the soldiers to wait a moment because está caliente (“It’s hot”). Today, a slightly modified version with olive oil and salt is Alergia’s most popular snack.

The region’s historic Jewish community (now mainly departed after Israel’s founding) also left an indelible mark on its cuisine. Unable to cook during the Sabbath, local Jews set aside dishes of vegetables, grains, and meats to be slow-cooked overnight ready in time for the Sabbath’s end. These dishes are called dafina (meaning “covered”) and are still prepared by Jews and Muslims.

A striking thing about North African cuisine is the artistic presentation of dishes inspired by Islamic geometric patterns and Arabic calligraphy, perhaps sometimes subconsciously argues Koehler.

The geometric pattern is used to align dates on a plate or decorate sweet couscous with lines of cinnamon. This visual flourish is most salient in the ineffably delicious Tunisian assida zgougou, an Aleppo pine nut pudding prepared for Mawlid al-Nabi (the birthday of the Prophet Muhammad) whereby families exchange their bowls of zgougou topped with a pastry cream that serves as the bed for an immaculate pattern of ground almonds, hazelnuts and pistachios.

Source : New Arab